Hopsewee Plantation – the Owners

Hopsewee Plantation, South Carolina’s First National Historic Landmark, is a preservation rather than a restoration and has never been allowed to fall into decay as it has always been cherished. Only five families have owned Hopsewee, although it was built almost 40 years before the Revolutionary War.

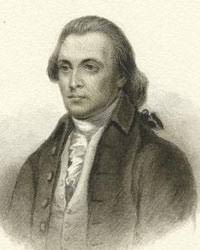

Thomas Lynch, Sr.

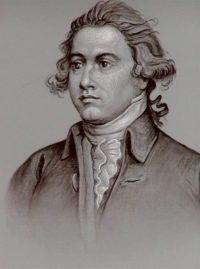

Thomas Lynch, Jr.

Hopsewee Plantation – Ownership Timeline

- 1735 – 1740s: Thomas Lynch I, began construction of the home that still stands as Hopsewee but died in 1738, passing Hopsewee to his son, Thomas Lynch, Sr. Lynch Sr. and his wife Elizabeth Allston, of Brookgreen Plantation, made Hopsewee their home.

- 1749: Thomas Lynch, Jr., was born at Hopsewee on August 5th. Thomas Jr. would be one of the three signers of the Declaration of Independence from South Carolina.

- 1762: Thomas Lynch, Sr. sold Hopsewee to Robert Hume for £5,000.

- 1766: Robert Hume died, leaving Hopsewee to his young family.

- 1841: John Hume, Robert’s son, died, leaving the property to his estate, including his children and grandchildren.

- 1844: The estate put Hopsewee up for sale, and John Hume’s grandson, John Hume Lucas, became the highest bidder.

- 1853: John Hume Lucas died, and his wife and children only returned to Hopsewee for holidays, hiring an agent to continue rice production.

- 1861–1865: During the Civil War, Hopsewee was looted, and rice was never grown again after the war.

- 1945: The descendants of Robert Hume held Hopsewee until 1945.

- 1969: Mr. and Mrs. James Maynard acquired Hopsewee Plantation, renovated the building, and opened it to the public in 1970.

- 2001: Frank and Raejean Beattie purchased Hopsewee Plantation and have owned it since January 2001.

The Senior Lynch was a distinguished public servant and one of the most important Santee River planters. As a prominent Indigo planter, he was the first President of the Winyah Indigo Society founded in 1755.

Thomas Lynch Jr. was the second youngest signer of the Declaration of Independence at 26 years of age and thus gave his birthplace, Hopsewee Plantation, a place in American History.

Lynch Family

Hopsewee Plantation sits atop a bluff overlooking the Santee River with one entrance facing the river and the opposite entrance facing the road which winds along the river. Originally there were several hundred acres of rice land to the south in the mile-wide delta, across the river from the house.

Hopsewee Plantation was originally part of the lands owned by Thomas Lynch, I (deceased 1738). He owned most of the land from Hopsewee to the ocean and Hopsewee was the first of his seven plantations on the North Santee River. He also owned Blessing Plantation on the Wando River. Hopsewee Plantation was chosen of all the Lynch properties for the family home of Thomas Lynch, Sr. (1726-1776).

Hopsewee overlooks the beautiful Santee River and the rice fields which were its source of income until the Civil War. Lynch Sr. was married to Elizabeth Allston, of Brookgreen Plantation, another prominent Georgetown family, and they had two daughters Sabina (b.1747) and Esther (b. 1748) and one son, Thomas Lynch, Jr. (b. 1749) After Elizabeth Allston died (c. 1750), Mr. Lynch married Hannah Motte, and they had a daughter, Elizabeth (b.1755).

-

Slave Cabin

-

Slave Cabin

-

Slave Cabin

In 1850 the Georgetown Census showed Hopsewee Plantation had 178 slaves and produced 560,000 pounds of rice.

Hume Family

In 1762, Thomas Lynch, Sr. sold Hopsewee to Robert Hume, who considered it just another rice property. He never lived there and died only four years after purchasing Hopsewee. Robert had two sons, Alexander and John, who was only two years old when the family bought Hopsewee. Robert bequeathed Hopsewee to his older son, Alexander. When Alexander died at the Siege of Savannah, the plantation passed to John.

As a young man, instead of going bayonet to bayonet with the British, John joined the local militia and served under Francis Marion (the Swamp Fox) during the Revolutionary War. After the war, the John Hume family lived at Hopsewee in the winter and Charleston in the summer. He died in 1841 leaving seven children and several grandchildren.

In 1844 the Estate of John Hume advertised “That Plantation called Hopsewee” for public sale for a division among his heirs. The successful bidder was his grandson, John Hume Lucas, who became a very successful rice planter.

John Hume Lucas was the grandson of both John Hume (through his father) and Johnathan Lucas (through his mother). He inherited both wealth and innovation.

Rice Barn

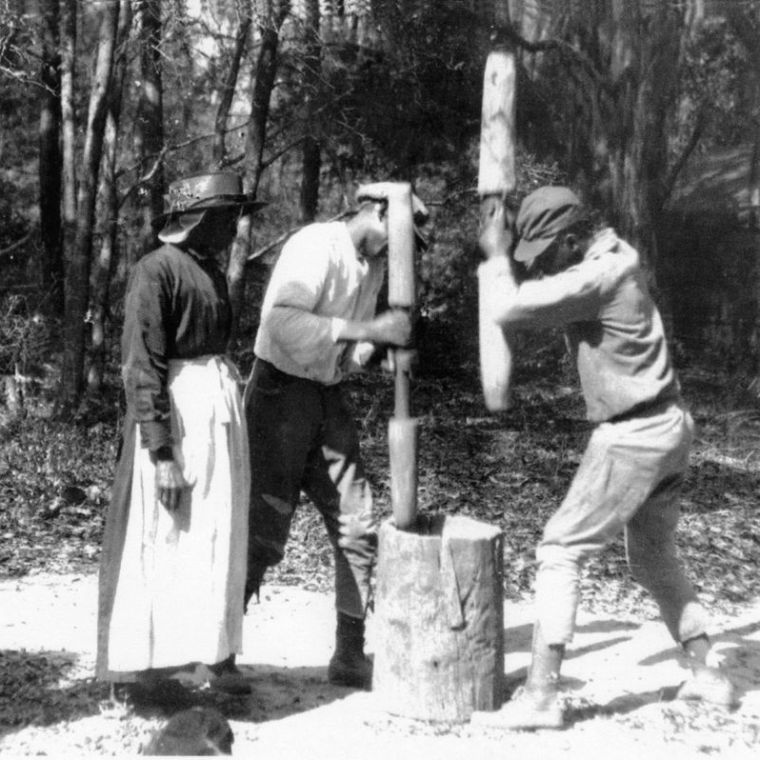

Hoeing Rice

Huling Rice

John Hume Lucas

- From the Hume family, John inherited land, social status, and connections.

- From the Lucas side, he inherited technical know-how, access to rice milling technology, and possibly direct involvement in the Lucas family’s milling enterprises.

The plantation remained successful in production through an agent until the War Between the States. The house was beautifully furnished, but at the time of the evacuation of Charleston, the Yankees plundered Hopsewee and divided everything they did not want for themselves among the former slaves.

A large number of the former slaves remained on the property, they continued to work on land and rent the property they remained on. William Lucas, the eldest son of John Hume Lucas and his wife, Mary Doar Lucas, returned to Hopsewee in 1900 where they lived until his death in January, 1914.

In 1935 Mrs. William Lucas wrote “Now the old house is closed and has been for twenty-one years. Will it ever be opened again? Not for the Lucas family in whose possession—and the Humes—it has been for nearly two hundred years. It is taken care of and, as much as possible, kept in order, but this once quiet place is now on the Georgetown to Charleston Highway, which goes right through the property, within a short distance of the residence.”

John Hume Lucas’ descendants held Hopsewee until 1945 when they sold it to International Paper.

In 1866 the planters, who had left their homes as wealthy men, returned poverty stricken and tried to take up the old life on the abandoned plantations.

There were still three slave cabins standing and an old man was living in one of the cabins, still plowing the corn field with an ox.

Wilkinson Family

In 1945, the heirs of John Hume Lucas sold the property to International Paper. Two years later, Colonel Reading Wilkinson and his wife purchased the house and a few acres surround the house, and modernized with plumbing, heat and electricity. Their son, Phillip Wilkinson, recalls there was an elderly black woman living in one of the cabins near the house when he moved there as a young boy. There were still three slave cabins standing and an old man was living in one of the cabins, still plowing the corn field with an ox. The house remained under their ownership for over twenty years.

-

Early 1900's

-

Wedding at Hopsewee

The Maynards obtained the National Historic Landmark status of the property in 1972 and opened their home as a house museum

Maynard Family

After Mrs. Wilkinson was widowed and her children grown, she traded houses in 1969 with James T. and Helen Maynard. Mrs. Wilkinson moved to Meeting Street in Georgetown and Mr. and Mrs. Maynard moved to Hopsewee Plantation with their two daughters Cassie and Betts.

The Maynards renovated the historic home and, importantly, opened it to the public in 1972, beginning its life as a house museum. They were also instrumental in securing Hopsewee’s listing on the National Register of Historic Places (1971) and its designation as a National Historic Landmark (1972) The Maynards operated Hopsewee as a museum and historic site for over three decades, from 1972 to 2001.

Their legacy is clear—they transformed Hopsewee into a public historic treasure, preserving architectural integrity and fostering community engagement.

The Maynards were approached by many developers who desired to develop the waterfront property. However, the Maynards were reluctant to see the property they loved and cherished for thirty years suffer this fate.

The Beatties have clearly built upon the foundation laid by prior owners, actively shaping Hopsewee into a living site where history, culture, community, and hospitality come together. Their work ensures the plantation remains not only preserved—but also accessible, educational, and deeply connected to its rich Lowcountry roots.

Frank and Raejean Beattie - 2001 to present

In the Fall of 2000, understanding the property had been sold, Frank Beattie stopped by Hopsewee to wish the Maynards well. When the Maynards told him they had not sold the property to a developer and wanted someone to have the property who would love it the way it had been since before the Revolutionary War, he was pleased to take on the responsibility of caring for Hopsewee. Frank and his wife, Raejean, view their ownership of Hopsewee Plantation as a gift from God and a trust to the people of South Carolina and the United States.

In January 2001, Frank and Raejean Beattie became the fifth owning family of Hopsewee, after the Maynards. They originally lived on-site in the main plantation house, maintaining it as their private residence while still welcoming public visitors

In 2006, they placed a conservation easement on approximately 56 acres of the property with the Lowcountry Open Land Trust, legally protecting the house and grounds from future development. They have since purchased adjoining properties to increase the footprint of the plantation to over 100 acres.

They’ve overseen important restoration projects, especially concerning the on-site slave cabins. Skilled craftsman David Fegley reconstructed two original cabins using traditional techniques.

In 2008, they opened the charming River Oak Cottage Tearoom. Named one of South Carolina’s top tearooms, it provides a full Southern Tea Service, Lowcountry-inspired lunch, and even evening “Wine by the River” events with hors d’oeuvres overlooking the North Santee River.The menu, and Southern Tea Service, are recipes crafted and overseen by Raejean Beattie, herself a gourmet cook and Lowcountry cuisine enthusiast.

-

River Oak Cottage Tea Room

-

River Oak Cottage Tea Room

-

River Oak Cottage Tea Room

Under the Beattie’s stewardship, Hopsewee has grown to welcome over 10,000 visitors a year. They have enhanced visitor experiences by offering more than house tours: they’ve introduced Gullah cultural tours, built the River Oak Cottage Tearoom and the Hopsewee Historic Museum, offer Sweetgrass Basketmaking classes and Indigo Dyeing workshops, and many other seasonal events.